Years ago, when I was struggling with addiction, I would occasionally (once a month or less) engage in sex work to help make ends meet. This was voluntary — no one made me do anything I didn’t want to do — but it’s still uncomfortable for me to think about sometimes. I always used protection during these encounters and continue to get screened for S.T.D.s regularly. If anything, I think I’m slightly less likely than the general population is to pass anything on.

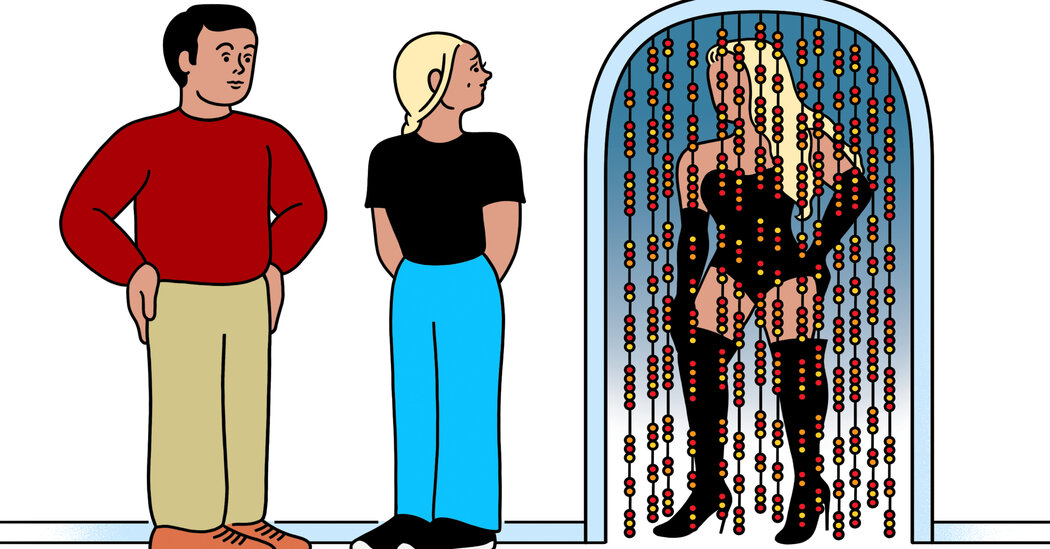

I’m in a new relationship that’s starting to get serious. He knows about my past issues with addiction. Do I have to disclose the fact that I used to be a sex worker? He’s been very accepting about everything up to this point, but as a woman I’m aware that there’s so much social stigma around sex work that I think there’s a chance he might end the relationship if he knew about this. Even if he didn’t end the relationship immediately, I imagine it would make him incredibly uncomfortable. I really don’t want to ruin a good relationship over something that ended five or six years before we met. But I feel as if I’m keeping something important from him.

Exactly how much about my sexual past does my current partner have a right to know? For that matter, what about anyone I might date in the future? Twenty years from now, is this still something I need to disclose? — Name Withheld

From the Ethicist:

The stigma around sex work you mention is real enough, and has multiple sources. Part of it is surely a spillover from times when people thought all extramarital sex was wrong. And then, for many, sexual intimacy has a special kind of significance, such that engaging in it for any reason other than as an expression of desire is upsetting. Some negative associations, too, arise from the fact that much sex work is not fully consensual, even though the wrong there is done to, and not by, the sex worker. Despite the medical facts you mention, concerns about disease can merge with inchoate notions of moral pollution: The sex worker is seen as tainted, contaminating the social body.

These perceptions are highly gendered. Women’s sexuality has traditionally been far more strictly regulated than men’s. That’s why there’s no male equivalent of the ‘‘fallen woman,’’ and nobody talks about ‘‘easy men.’’ Recent fictional, and autofictional, depictions suggest that these patterns persist. When the novelist Justin Torres writes about male sex work, there’s little sense of it as character-defining or tragic; it’s one of the curious odd jobs you might take to get by. By contrast, it weighs heavily on the human rights lawyer in Sally Rooney’s latest novel that his girlfriend has been ‘‘borderline what you might call a sex worker.’’ Social stigmas are readily internalized, so you’ll want to come to grips with your own discomfort. I hope it comes from your having put yourself in the situation where you did something you feel you can’t freely talk about — and not because you see yourself as a sexual sinner.

Thinking all this through will help you get a handle on what your own attitude is and should be; it doesn’t settle what you owe to your partner. Most people today don’t expect a partner to reveal details of their earlier sexual lives. This doesn’t mean there aren’t things about your sexual past that partners would feel they ought to have been told. If your partner would be upset by learning about your sex work, you can assume that this is one of the things he wouldn’t want withheld from him. Yet that’s not the same thing as his having the right to know. Most people have done things in their past that they’d rather keep to themselves. You don’t have a duty to announce them all when you enter a serious relationship. And if, with the passage of years, this episode in your life recedes in significance for you, so would the rationale for discussing it.